Union City Schools Find Ways to Help Immigrants Succeed

|

Chiung-En Chen taught children how to count in Mandarin through song this month at Eugenio Maria De Hostos Center for Early Childhood Education in Union City, N.J. PHOTO: STEVE REMICH FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL By LESLIE BRODY Nov. 14, 2016 4:00 p.m. ET |

UNION CITY, N.J.—Jocelyn Encalada, a high school senior, arrived a year ago from Ecuador with limited English and a daunting road ahead.

She misses her mother, who stayed behind, and lives with her father, a factory worker. But after bilingual classes and a job at a bank, Ms. Encalada’s hopes are high as she applies to Columbia University. “I want to be the first in my family to graduate from college,” she says.

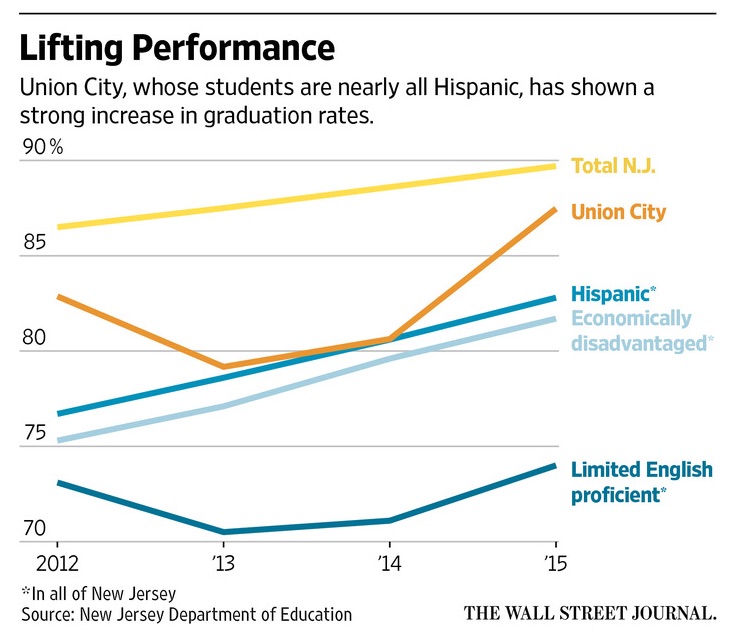

Union City schools have become a model for ushering low-income English-language learners into the mainstream. Almost 96% of its students are Hispanic, and many live in Spanish-speaking homes. Officials estimate at least 15% of students are undocumented.

Even so, the district’s 87% graduation rate in 2015 nearly matched New Jersey’s overall. A study from the Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis this year found that on standardized math and reading tests, Union City students performed about a third of a grade level above the national average, although the area had a median family income of $37,000.

Educators have come from Canada, Norway and several states to see how this system for more than 14,000 students succeeds. A New York City team planning Mayor Bill de Blasio’s prekindergarten expansion toured Union City’s public preschools, where 3- and 4-year-olds sing songs in Mandarin.

Superintendent Silvia Abbato credits the system’s “slow and steady” efforts to continuously improve, rather than trying to force a quick transformation. “We don’t remain stagnant,” she says.

Back in 1989 the district was floundering on the brink of a state takeover. Administrators and teachers banded together to update curriculum and devise tests to diagnose students’ needs. They deployed master teachers to help others get better and instituted student uniforms to bolster a sense of mission.

They also started bilingual classes that helped immigrant children become literate in their native language and English at the same time. A fourth-grader who arrives without knowing the alphabet, for example, has gym and music with fellow fourth-graders while getting English- and Spanish-language instruction in small groups of up to 12 children.

In a bilingual chemistry class at Union City High School on a recent morning, 10th-graders wearing goggles listened to a teacher who questioned them in English but flipped into Spanish when necessary. One student needed a classmate’s help with vocabulary to explain in English what he was doing with several small objects. “Measuring the mass,” he said slowly.

Ms. Abbato, who arrived from Cuba at age 9 speaking no English, attended Union City schools and in the past 36 years rose from teacher and principal to district chief. Many top staff and teachers have also lived in the city and worked in its schools for decades.

“Everyone knows each other,” says Adriana Birne, director of early childhood programs and Ms. Abbato’s twin sister. “It’s a culture that’s been built and a community.”

To be sure, the district struggles with chronic urban problems, including absenteeism, transient families and teen pregnancy. But there is a scrappy resourcefulness in this roughly one-square mile district on the far side of the Lincoln Tunnel from Manhattan. When a new elementary school opened, the superintendent knocked on neighbors’ doors asking if she could rent their parking spaces for teachers.

“We’re just the right size,” says the superintendent. “When a district is too large you lose your identity.”

David Kirp, a professor of public policy at the University of California at Berkeley, spent more than a year in Union City researching his 2013 book, “Improbable Scholars.” He points to its high-quality preschools, word-soaked classrooms, coherent curriculum, use of test data to address students’ weaknesses, parent outreach and a “culture of caring.”

“Running an exemplary school system doesn’t demand heroes or heroics, just hard and steady work,” he wrote. Mr. Kirp contrasted that approach to turnaround strategies in cities that relied on closing schools, removing teachers and launching charter schools, often sparking intense conflict. Union City has no charters.

The district has long treated schools as neighborhood hubs. It offers three free meals a day to students, health clinics, and frequent parent workshops on immigration and other issues.

Union City gets additional state aid due to a New Jersey Supreme Court ruling that requires poor cities to get help providing an adequate education. It spent $19,788 a pupil in 2014-15, slightly more than the state average.

Frank Alonso, a parent who went to the city’s schools himself, said that as a retail executive he could afford private schools but prefers the public ones. “I remember when we were in little trailers,” he says. “Now we have computers and computer classes. I’m proud of the system.”

Write to Leslie Brody at [email protected]